Missing and murdered indigenous women in the USA

A search for clues in one of the poorest reservations in the USA.

Murder is the third most common cause of death among indigenous people in the USA. Above all, women are murdered or reported missing. There are many reasons. Alcohol and drugs almost always play a role. Men and young men are also victims. The poor Pine Ridge Reservation in the state of South Dakota is particularly affected.

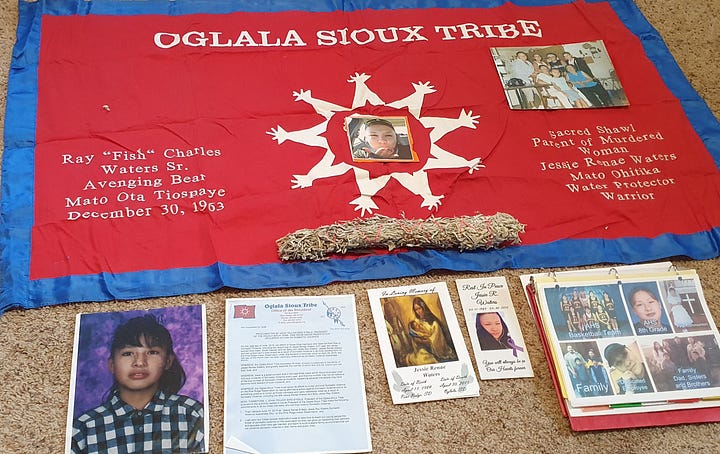

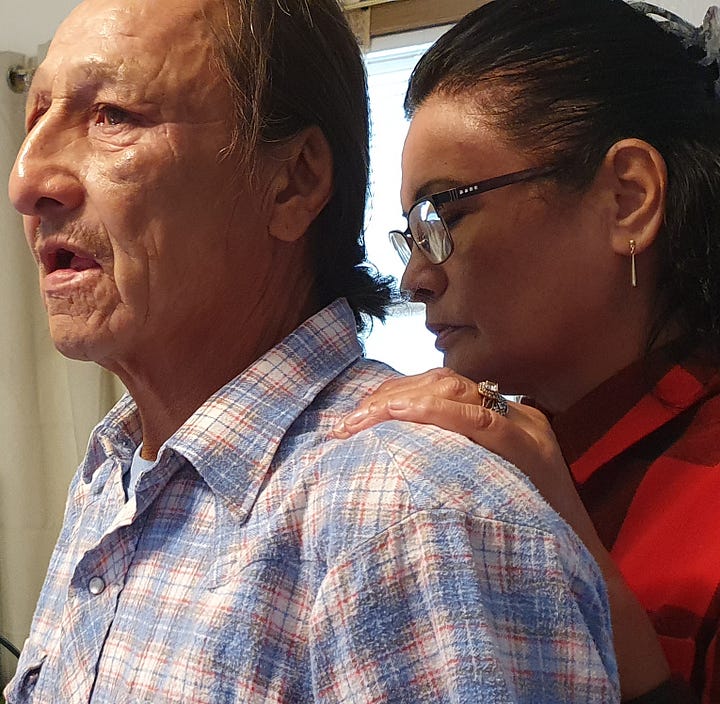

Pine Ridge Reservation in the US state of South Dakota, in the living room of Raymond, Ray for short, “Fish” Waters. The small, petite man with an eagle nose, his long black hair tied back in a plait, is a so-called sundancer. He performs spiritual dances and rituals. He has spread a red cloth on the carpet in front of him. On it are photos of his daughter Jessie, who was murdered in April 2015. She was 29 years old and three months pregnant.

“At night time. Thunder, lightning, rain, wind. I got a call from my older brother. He told me: be strong. They found a woman dead in Oglala. They think it’s Jessie. I knew it was her”.

Jessie Waters is one of countless murdered indigenous women in the USA. Their risk of becoming a victim of violent crime is significantly higher than the national average. As Ray “Fish” Waters slowly fans the smoke from a bundle of sage back and forth, a tear rolls down his cheek. “After the murder of my daughter the grief rolled over me. She always told me: ‘Dad, we look up to you, you got to hold it together for better or worse.’ Thank you, Jessie Renee Waters”.

An hour’s drive away, Lisa Lone Hill sits in a wheelchair in the shade of a tree. She has had many operations, looks fragile and much older than 60. Her daughter Larissa has been missing since 2016. She was 21 when she disappeared. “She texted my niece that she was with these two guys – and that was the last time we heard of her. That was on October 3. “

“Althought my health is not to good, I hang in there. Hoping I don’t die not knowing what happened to her. I still miss her every day”.

Lisa Lone Hill

Larissa lived with her one-year-old daughter in Rapid City, 130 kilometers away. She had alcohol problems and was repeatedly caught shoplifting. “There were rumor she overdosed on Meth and died of her own vomit”, says Lisa Lone Hill. “And these two guys then put her in the trunk of the car and brought her down to the rez. Two guys were supposedly seen carrying a trash bag. They said they were going to bury a dog but the trash bags were too big for dog”.

The long shadows of the past

An estimated 30,000 people live on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The administrative center is Pine Ridge with a population of around 3,000. Susan Shangreaux runs the victim center of the Oglala Lakota tribe here. The sociologist, a plump woman with short hair and dark glasses, worked as a prosecutor for the tribal administration for eleven years. She collected evidence gathered by the tribal police for presentation in court. Many acts of violence have their roots in intergenerational trauma, says Susan Shangreaux. Triggered, among other things, by the system of boarding schools, in which indigenous children were to be re-educated as young whites, in some cases until the 1960s. Many were not only beaten and humiliated, but also sexually abused. “The sexual abuse was done to our grandparents and great grandparents. I would say 40 percent bring it back to the families. Our grandmothers are now passing away and they are the ones shared cultural and their wisdom. And the grandfathers, those are men who were hurt really so bad that they didn’t care anymore, they just drink”.

When Susan Shangreaux looks out of the window in her office, she can see the misery that has grown out of it. Here, in the city center right next to the post office, petrol station and supermarket, is the meeting place for the homeless. It is also a hotspot for crime, alcohol, drugs and rape. Even men are raped, reports Shangreaux. Because many parents are addicted to alcohol or drugs or are in prison, their children grow up with their grandparents. Human trafficking in these children is flourishing, with grandparents often outright selling their grandchildren. “All this sexual abuse going on is covered up by those grandmothers. They don’t want to see their grandsons or their own sons go to jail. It is kind of a shame issue. So their granddaughters are hushed up.” They hush up, also their own shame and keep it inside them”.

The survivor

“Growing up in a Lakota home with virtues and values you are not supposed to see a man hitting a woman. And when it happens nobody talks about it”, says Esther Wolfe. The women would not stand up and speak out what has been done to them. “I also was ashamed at first, I was scared. But I realized that I need to speak out because I could save some younger women who are trying to get away.”

Esther Wolfe is a so-called survivor. A slim woman with long jet-black hair. She was reported missing by her family on July 4, 2019. She was 20 years old at the time and had left her boyfriend after three years of domestic violence, so her sister reported him. After he had served his sentence, her ex-boyfriend abducted her in a car to the Pine Ridge Reservation, where they had both grown up.

“He grabbed me from behind and choked me until I was unconscious. For two hours I’ve got choked – all the way, the whole time. His his brother was driving, and his five-year-old nephew was in the passenger seat watching in all.”

Esther Wolfe

When they arrived at her ex-boyfriend’s home, a trailer, her brother and nephew drove away. Esther Wolfe remained in the power of her former partner – for nine days, during which he did unimaginable things to her. “He just beat the living daylights out of me. I had a broken jaw, a broken pelvis, eleven broken ribs, a hamatome on my face, and my eyes were bleeding. There was a garland of Xmas lights somewhere, and he wrapped them around my neck and hung me. He was raping me like everything. I couldn’t even lift up my own body. I never felt so helpless.”

Assistance for victims and families

At the Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Services in Pine Ridge, Susan Shangreaux and her co-worker Jackie help women like Esther get out of abusive relationships. They apply for protection orders and place victims in the only women’s shelter on the reservation. The perpetrators, the men, are looked after by 60-year-old Milton Bianas. The tall, massive man with the gray Lakota braid is a probation officer. He also conducts anti-aggression training – for men and women.

99 percent of the men and the women who get to this point are involved with alcohol or drugs, says Bianas. Most times it is because they are stressed, and the only outlet they know is to get drunk or get high. “It’s an excuse for them. Not for me. And this is what I teach. I ask them: ‘How many believe that you are Lakota?’ They raise their hands. ‘So why you’re drunk? Why you are you a drug addict? Respect yourself! No alcohol and no drugs!’”

Milton Bianas knows what he is talking about. He himself was once where his clients are today. When the court gave him the choice of going to prison or Alcoholics Anonymous and taking part in anti-aggression training, Bianas opted for the latter. He later became a police officer specializing in domestic violence and child abuse. He teaches the young men in his training that they should reflect on their Lakota spiritual roots instead of following the “white man’s” concept of masculinity: “Be a man! Don’t be afraid! Go knock them out! Go kick their butt! Here, drink up! Don’t let her treat you that way, you are the man in the house!”

“To be a man and have courage in the Lakota tradition means on the other hand: standing up and saying No”.

Milton Bianas

„Hey brow, let’s hit this meth, I’ve got some Fentanyl!“ “No, man, I’ve got to take care of my family.“ Bianas explains: “Why does that take courage? Because your friends will turn around and call you every name in the book for not doing it. And then, if you stay cool and refuse to fight them – that is courage”. According to Bianas, the Lakota tradition also includes the courage to leave the reservation in order to pursue a career or study, for example. Indigenous people have their tuition fees waived by the US government. But instead of encouraging the young people, friends and family members often accuse them of thinking they are better than them. Some may then leave in secret to escape the shackles of social control and misery on the reservation.

Lack of data and prosecution

Lisa Lone Hill is certain that this was not the case with her daughter Larissa. “She would never just disappear not letting us know what happened to her. Maybe she was tortured. And I was not there to protect her”. Susan Shangreaux from the Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Services is also convinced that most of the missing persons are dead. How many there are can only be speculated. There are no exact figures. This is despite the fact that President Donald Trump signed the Savanna’s Act in October 2020. The law is named after a young pregnant indigenous woman who was murdered in North Dakota. Federal agencies working with indigenous tribes are to develop law enforcement policies and practices to prosecute or prevent crimes against indigenous people.

Two years later, a statistic lists around 10,000 reported indigenous missing persons. Most of them had reappeared. However, the study does not specify whether they are alive or dead. However, it points out that not every reservation would even report missing persons due to mistrust of the authorities. Even Esther Wolfe, who was so brutally abused by her ex-partner, initially did not want to file a report. She has her family to thank for the fact that her abuser now has to pay for his crime in prison, as they convinced her to testify in court. “It was the hardest thing I ever had to do. And during court he was kind of smirking and laughing as if it was a fucking joke. I had to leave the court room constantly because I was kind of hyperventilating. He had no sympathy and no remorse. I honestly had thought that time I was gonna die.”

After the death of his daughter Jessie, shaman Ray “Fish” Waters felt as if he had died with her. Little did he know that he would have to go through the same emotional hell a second time. Because two and a half years after Jessie’s violent death, his son Raymond Junior was also murdered. He was 24 years old. “The murder killed him with an axe while he was sleeping on the couch in the early morning hours and then set the trailer on fire”. His murderer was later sentenced to 35 years in prison. The alleged murderer of daughter Jessie, on the other hand, could only be proven to have set fire to her caravan weeks before her death.

In cases like this, vigilante justice seems to be an option for the Lakota. Lisa Lone Hill says about the alleged murderer of her daughter Larissa: “Those two guys ended up dead. One was killed in a car wreck, the other one was shot. I don’t know if this is mean but I think justice has been served. My cousin was saying I have to do something to those guys who had done this to me. And those guys died. I don’t know is this coincidence.” Ray “Fish” Waters had initially thought seriously about executing his daughter’s ex-boyfriend himself. Because he only had to serve four and a half years in prison for arson – and is now free again. An unbearable thought for Waters. Together with his other children, he wants to get the case reopened.

“The guy is still out there, free. We want him to be held accountable for her murder. He still has to pay the price somehow.”

Ray “Fish” Waters

Waters is hoping for little help from the police. The tribe does have its own police force on the reservation. However, in the event of a capital crime, the FBI takes over. A special unit of the tribal police then works with the federal police. The FBI is also responsible if the victim is a child under the age of 12. And if the perpetrator is not indigenous, but committed the crime on the reservation. Lisa Lone Hill and Esther Wolfe are bitterly disappointed with the police. “They weren’t really too much help”, says Lone Horn. “The cops said the cartels have Larissa, and we should get on with our lives, she will pop up.” And Esther Wolfe recalls: “They said they were looking for me but they get multiple calls like that from all those women. They rather just go to a call about a dog before they go for a call of a woman being missing.”

Susan Shangreaux at the Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Services often experiences that the chronically understaffed tribal police do not respond at all after an emergency call. On a wall in her office hang large wanted posters of missing and murdered women and girls. There are also two boys. Men also disappear or are murdered. However, due to time constraints, Shangreaux concentrates on the female victims. She has posted a seemingly endless series of cases on Facebook, many of which remain unsolved to this day. Shangreaux wants to reopen them – including those from the 1960s, when missing and murdered women were hardly an issue. She points to the picture of a smiling young woman in a smart white blouse:

"She was beaten by her husband. He ran her over when she was running for help with the two year old baby. And she carried an unborn. He hit her a second time and killed all of them. The husband is still free because this happened in 1963 and nobody pushed for it."

"This young girl was murdered by her boyfriend. His friends wrapped her body in a mattress, they tried to burn her, and then they threw her in s trashcan. That’s where her family found her".

"This one was brutally raped and beaten to death – and it even was a BIA investigator, he is from this tribe".

"This one is missing, she is only 12 year old".

"If I look into it... there is just, oh my gosh, story after story."Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

The phenomenon now officially has a name: Missing and Murdered Indiginous Women. MMIW for short. Awareness of this problem has grown considerably on the reservations since the coronavirus era, as domestic violence and child abuse increased enormously during the lockdowns. Indigenous activists have taken up the cause of beating the drum for the problem and giving survivors and bereaved families a voice. Tarah Weeks has been active in the movement since 2019.

“I think it’s more appropriate to call it Missing and Murdered Indigenous ‘Relatives’ because back home on my reservation the number for men is much higher than for women.”

Tarah Weeks

Tarah Weeks is a Navaho from the state of Arizona and runs self-defense courses for indigenous women and men. This time she is here for her second volunteer project: She has converted a truck with cargo trailer into a mobile search and rescue station. She uses it to support rescue teams and relatives in their search for missing persons. Weeks not only has blankets, generators and bandages in the van: she has also trained in first aid – and in how to avoid contaminating evidence and traces on site. She is now advising a community project on the reservation on how to set up such a unit and certify a team of volunteers. Although Tarah Weeks experienced domestic violence herself in her first marriage, she advocates a change in thinking in the indigenous community.

“I hate to use ‘trauma’ because it is a word that I feel is overused. We just keep on victimizing us in our own heads by calling it trauma, trauma over and over again. It can be an excuse for not progressing”.

TarahWeeks

Missing and murdered people can be found on all reservations, including in the indigenous communities in the cities. Poverty, high unemployment and broken family relationships encourage acts of violence. This is why the Pine Ridge Reservation is particularly affected. The tribal administration is weak, Susan Shangreaux also calls it corrupt. Connections are everything. “Every single one of those tribal council men and women, the tribal president, all of them are not college educated. They don’t know know to budget – but somehow they are in all these jobs. It is kind of hard to say this because I love my tribe but our own council have family members who are perpetrators”. Whether a perpetrator is prosecuted often depends on how big, meaning how influential, their family is, says Susan Shangreaux. There is also a complicity of silence. While Esther Wolfe was being held captive by her ex-boyfriend, a police search was underway. Newspapers and television stations showed her photo. “His mom, his dad, the whole family saw me, they all knew I was missing. His mother gave me pills against the pain”.

The tribes and the U.S. government

Almost everyone on the reservation knows a victim of violence – and many also know the perpetrator and his family. The father of probation officer Milton Bianas, for example, murdered his second wife. Nevertheless, many Lakota and tribal administrations identify those responsible outside their own community: The perpetrators are mostly white, they say. Or: the US government, the miserable living conditions or the Mexican drug cartels are to blame. Tarah Weeks, on the other hand, takes a stance that she believes is extremely unpopular: “There are many, many reasons why our relatives get missing or murdered, especially with the introduction of all these dangerous drugs that are poisoning our communities. But we can blame, blame, blame: in the end it comes down to each individual to make unsafe choices for themselves. We do have to take responsibility for ourselves and we we have to take responsibility for our people”.

Tarah Weeks and a group of indigenous motorcyclists do this in a very special way: together they go on tours to draw attention to the problem of the missing and murdered. They call their project the Medicine Wheel Ride. For example, they ride together every year on May 5. This day is the National Day of Remembrance for Missing and Murdered Indigenous People in the USA. The mother of a young woman who was murdered brought it to life in 2017.

The tribes and the U.S. government

November 26, 2019: President Donald Trump signs a decree for an interdisciplinary task force to work with indigenous authorities on the missing and murdered.

March 2021: Indigenous woman Debra Haaland becomes Secretary of the Interior in President Joe Biden’s administration. When she takes office, she wears moccasins and a traditional ribbon skirt. A special skirt with ribbons, which in indigenous culture is a symbol of women’s strength. Many activists have high hopes for the lawyer Haaland, as she has already campaigned for the issue of disappeared and murdered indigenous women as a member of parliament. Haaland says at a hearing in the Senate in May 2023: “That’s why I started the Missing and Murdered Unit at the department. Since its creation in 2021 it has investigated 681 cases and solved close to 240. We have 32 of 63 positions filled, they are a dozen of those units across the country”.

Susan Shangreux has the impression that the US government is doing more for the victims and their families than the tribal administration itself. Even though, according to the US Department of Justice, non-Indigenous people commit most assaults on indigenous women, Shangreaux believes the problem is homemade. “The problem is on this reservation. It is not the US government, it is not the FBI, it’s not church groups, it is not white people or black people or the Mexican cartels. It is with our police officers, with our tribal council. We just don’t have anyone who is willing to step up and stop the crimes. The problem is within our own tribe, it is our own people that are hurting each other”.

Ray “Fish” Waters wants to set up a self-help group involving family members of victims and perpetrators. Perhaps, he hopes, a process of reconciliation could begin. Lisa Lone Hill, who, like him, is involved in the movement for the missing and murdered indigenous women, wears a red and black leather bracelet with the inscription “No more stolen sisters!”. She also finds comfort: “We help each other. We tell our stories. It’s painful because it brings back memories.” Even for the survivor Esther Wolfe, the drama of that time is not yet in the past. She suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and has not been able to work regularly since. She was homeless for a short time and now lives with a friend. She does not have a boyfriend. “After what happened I was supposed to go to counseling but what I did: I drink. Honestly this is my second day sober. It is a start. I am scared of working because I was kidnapped from work. When it comes to men, I don’t trust them”.

What solutions are there?

Activists and family members march through Pine Ridge on a memorial march in honor of all the missing and murdered. The women carry placards with photos of victims and signs reading “Justice”. It was at one of these marches that Esther Wolfe met Susan Shangreaux and decided to go public with her own story.

Tarah Weeks appeals to all tribal administrations to finally get to the root of the problem: “There is a lot of talk about the need for recovery programs and treatment centers. Why do we not get rid of the problem from the start? Why not get the drug dealers off our land. Expell them. That’s how they took care of problems in earlier times. Then you get the opposition at once saying: ‘He has a family’! Well, I have a family too. There must be consequences, otherwise it just keeps growing and growing”.

Susan Shangreaux sees exactly that happening in the future. Even the spiritual elders of the tribe, all men on whom she had placed a lot of hope, are no help. “The tukalas are supposed to protect our tribe. They are the most respected men in the tribe. They don’t drink. But I see them going to different countries speaking about how beautiful our tribe is. It is not beautiful when we have so much crime, when we have so much victims, when we have children who are crying because they are hungry. Where are these tukalas? I don’t see them out here”.

Lisa Lone Hill in her wheelchair often thinks about the day when she will find out what happened to her daughter Larissa. She longs for this day as much as she fears it. “I worry about that when the time comes. I want to know. I’ve been waiting all this time. But then is this thought of knowing how she died, of what she went through. It is scary”.

As if the tribal administration had heard the complaints, its chairman has now declared a state of emergency on the reservation – because of the many violent crimes and the many missing and murdered people. The US government should drastically increase the budget for the tribal police. This demand is also being made to the Indigenous Minister of the Interior, Deb Haaland, to whom the Office of Indian Affairs reports. It will be interesting to see whether she will pass the test.

This story was first published as a radio feature in German.

Is it possible to get a copy of the recording of Esther Wolfe?