Have you always wanted to know who your ancestors were and where they came from? In the US state of Utah, the Family Search Library offers a unique opportunity to do just that. The world's largest genealogical data collection is free to use for scientists and private individuals alike - and also possible via home computer.

The Family Search Library is a modern light gray box-shaped building made of cement in the center of Salt Lake City. At the nearby Union Pacific Railroad Station, the tramway in the colors of the Stars and Stripes, the US flag, has its terminus. “Find your story inside”, reads a banner on the outside wall of the library next to the entry. Inside the building, you can explore your own family tree on five floors.

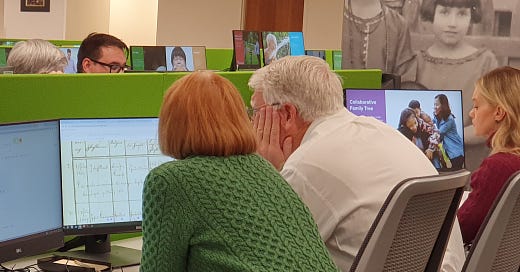

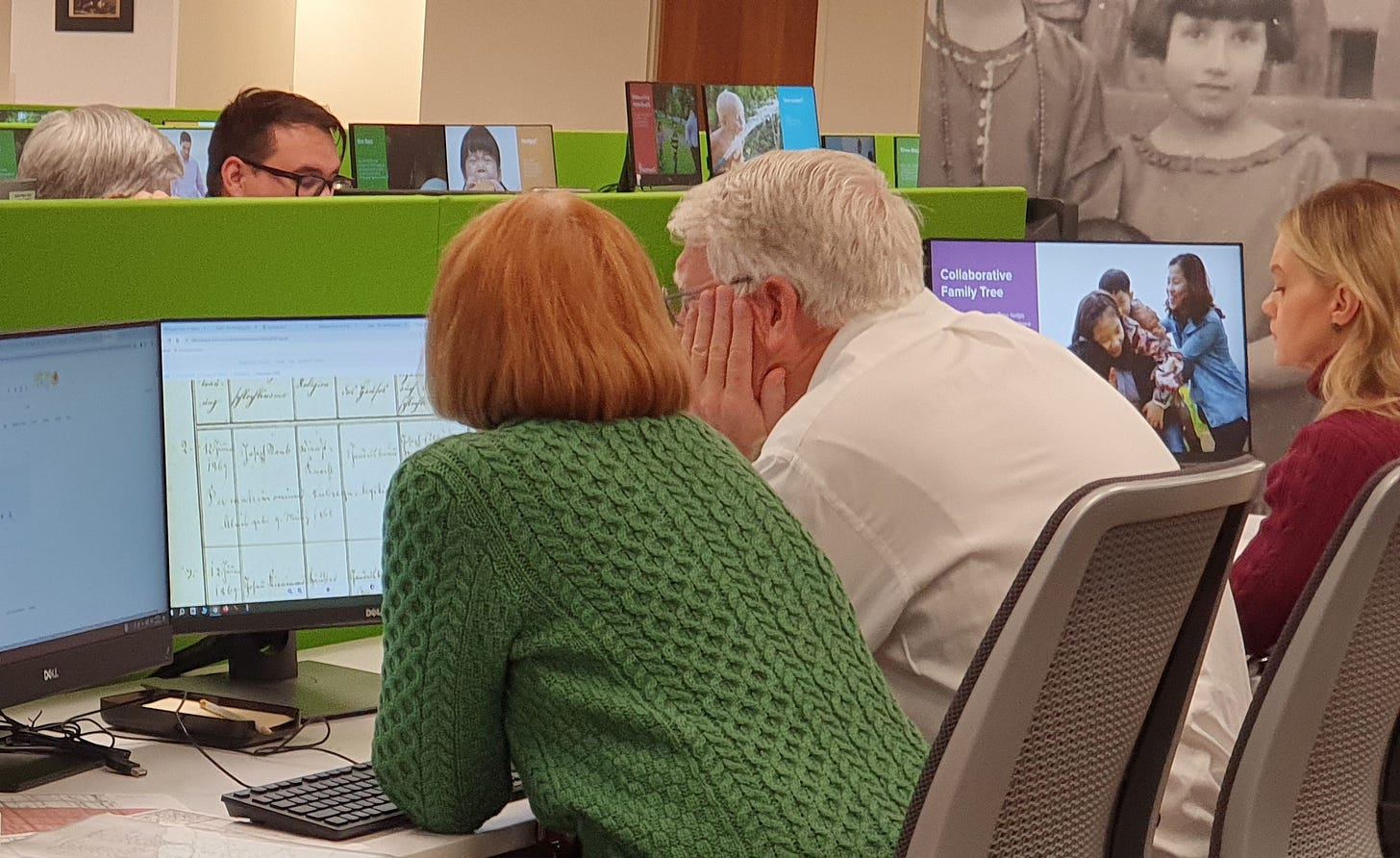

“I am from California and this is maybe my 12th, 13th visit. I come at least once a year.” Susan Negli, short red hair and rimless glasses, sits at one of the 350 digital workstations in the library. There are three flat-screen monitors in front of her. As these obviously are not enough for her, she has also opened her own laptop. “I always say I started genealogy when I was 15”, she begins her story. “My dad would walk me through the cemeteries and point out the ancestors when I was very little. With about 15, I took a piece of paper and I started to make lists. That was 60 years ago. It is a bit of a obsession. A hobby.”

The Family Search Library is run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints - commonly known as the “Mormons”. Its headquarters is in Salt Lake City, Utah - a vast area downtown. There you can find the cathedral-like “Temple”, a conference center and a round concert hall where the Tabernacle choir rehearses every Sunday, which is then performed and broadcast live on TV. The library is across the street.

The genealogical research of the Church began in 1938. The Family Search Library opened in 1985 and today houses the largest genealogical data collection in the world. Visitors can search for deceased persons under 13 billion names. And new ones are constantly being added. Research specialist Becky Adamson, who shows me around the library, explains the church doctrine behind this gigantic project: “We believe that families are together for ever, their relationship continues beyond death. So we create this family chain of eternal relationships.”

To this end, the church also practices the ritual of “baptism for the dead”. Living members are baptized on behalf of deceased persons who were not members. This is intended to enable them to enter “the kingdom of heaven” after all. It dawns on me: the belief in baptism for the dead is the main motive for the genealogical research. Critics from church ranks, not only in the USA, see this as proselytizing beyond death. Ralf Grünke, press spokesman for the Church of Jesus Christ in Germany, will explain to me later in a Zoom meeting: “We actually believe that a person obviously dies with their body, but lives on in spirit and can continue to make decisions. Baptism for the dead should therefore only ever be understood as an offer to the deceased, not as an automatic procedure.”

Nevertheless, there were protests, especially against the fact that some members went so far as to baptize Jewish Holocaust victims. The church has officially distanced itself from this. However, baptism for the dead, which may only be performed in so-called temples, remains an important practice of the church. Its interest goes far beyond merely collecting data, emphasizes press spokesman Ralf Grünke. “We want to create the largest family tree in the world and show that we are all related and connected. I think there is hardly a more important message at a time when differences along religious, political and ethnic lines are increasingly emphasized.”

A unique storage facility was set up back in the 1960s so that the information collected could be preserved even in the event of a disaster. It is located in Little Cottonwood Canyon, about 20 miles southeast of Salt Lake City, in the Wasatch Mountains. The cement grey color of the entrance building blends in perfectly with the surrounding granite rock. The mountains are a popular day trip destination all year round, but very few skiers and hikers have any idea of the gigantic collection of data stored here in the Granite Mountain Record Vault. “A yellowish-painted, earthquake-proof tunnel over 650 feet long leads into the granite mountain. There are thousands of archive boxes here in which the film material is stored. At 60°F and 30 percent humidity. Summer and winter. Protected in six underground vaults. Locked by a 14-ton steel door, secured on microfilm, protected from acid rain and radioactive radiation,” according to a radio report. The complex construction work took six years. Financed by the members of the church, who give ten percent of their salary to the church (voluntarily, I have been assured). Out of curiosity, I drove to the underground vault before I visit the library. However, I was only able to see it from the outside and from a distance. “Private road. No trespassing,” warns a sign next to the access road, which is also blocked by a white and red barrier.

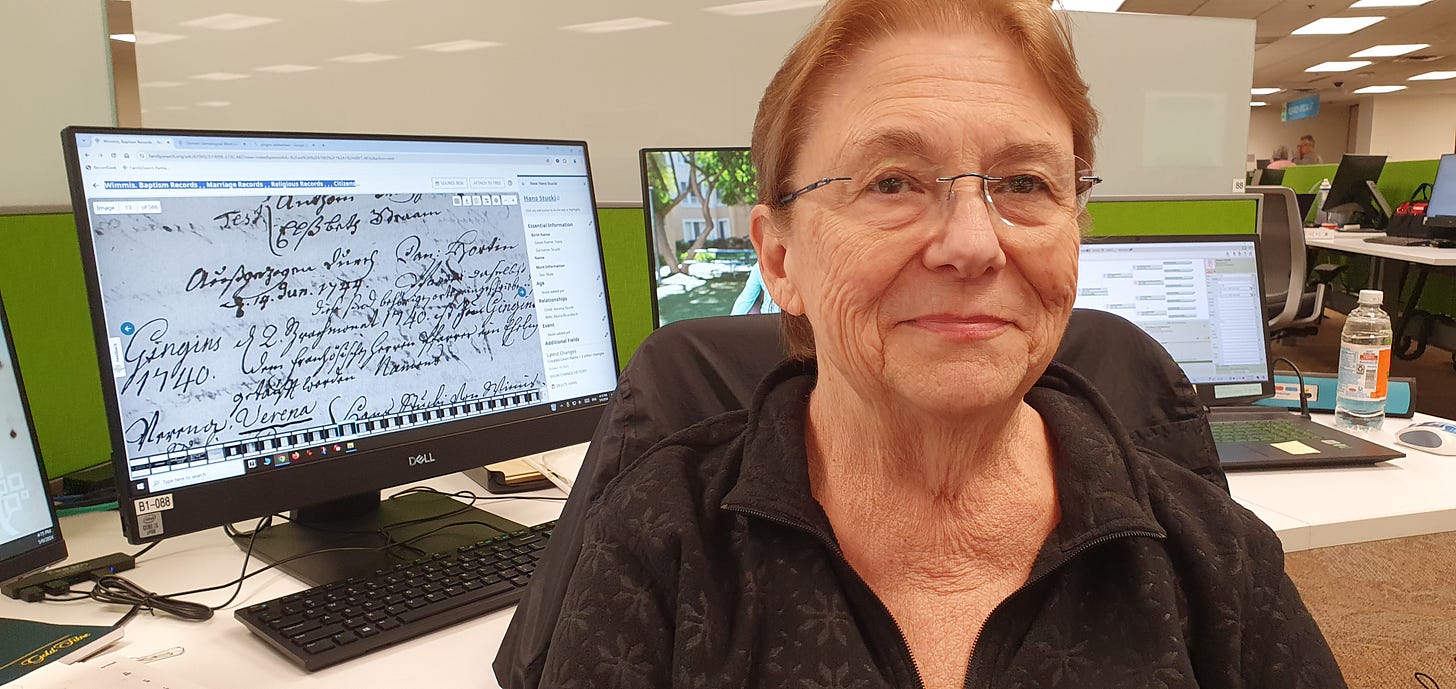

The Family Search Library in downtown Salt Lake City, on the other hand, was built especially for the public. “For example, I go to the “Search” function here”, explains a friendly blond woman the first steps to me on the monitor. “You can also switch it to German and many different languages, so you don't have to know English.” Beatrice Kopp from Switzerland is one of the many volunteers who help in the library when someone gets stuck in a search or needs technical instruction. Kopp was three years old when her parents joined the Church of Jesus Christ. Now, after her retirement, she helps out in the library with her knowledge of German and French. Other volunteers from the Church of Jesus Christ are currently trying to bring documents to safety in Ukraine before they are destroyed by the war.

“We call each other “sister”. We call each other “brother”. Because we really think that we are all, all of us - including you - children of God”, says Beatrice Kopp. No matter what country, she continues: “I go to one of our churches - we call the local churches “congregations” - and you immediately feel like brothers and sisters.” The strong sense of community stems from the founding history of the Mormons. In the early years of the church in the 19th century, its members on the east coast of the United States were severely persecuted. After the lynching of church founder Joseph Smith, many fled west until they found “their place” in Salt Lake City in 1847.

More than 600,000 books, 5 billion images and 2.4 million rolls of microfilm have been digitized to date. You can also search for your ancestors on analog microfilms and microfiche. Or in centuries-old, handwritten family and church registers that are lined up on long shelves. Sarah, round-faced and pony-tailed, is scanning a pack of family photos. “My mom, they had a house fire and they lost all of their pictures. So anything they’ve found at all I digitized first thing. I don’t want that to happen to my husband’s family or our own family.”

Like everything else in the library, the scanner is the latest technology. “It actually takes the picture of both sides at the same time. So if you have your photo labeled on the back, you don’t have to put it back and turn it over.” Sarah points at a stack besides her. “There are probably 600 pictures there. I did that in one hour and a half.” Behind a glass partition I can see the department where up to 40 books can be digitized in a day. Research specialist Becky Adamson shows me the long rows of drawers with microfilms and rolls out a family tree scroll more than ten feet long.

I stop by again to see Susan Negli, who is still sitting in front of the four monitors. Unlike Sarah, she is not a member of the Church of Jesus Christ: “I am not. I am not”, she assures me. Negli is happy when she sees me, because she is trying to decipher the first letter of a word in Old High German script. “My surname, Negli, is German-Swiss. … … You speak German! What is that letter right there? It’s about 300 years old”. To me, the letter looks like a B. I tell Susan so. She is delighted. Because “B” fits exactly with what she has researched herself.

Beatrice Kopp is also still around and shows me how to insert a roll of microfilm into the player. The Swiss will stay in Salt Lake City for a whole year. Such international voluntary services are common for members of the church and are part of the worldwide missionary service, she explains. “What I've already experienced here! Where I say, I can't believe how quickly you find people.”

Research specialist Becky Adamson logs into the system to demonstrate what is possible with her own family tree. The ramified line of ancestors appears on an oversized touchscreen. When Adamson swipes her finger over some of the names, a world map opens showing where these ancestors lived and what it was like when they were alive. are recipes of typical dishes of the region, and even which of your ancestors you look most like.

“We believe that knowing our family stories can strengthen the descendants”, says Becky Adamson with conviction. “A lot of people when they come here and learn about the stories and see pictures they develop a love for their ancestors. That creates a bond - whether you are a member of our church or not.”

For this text, I have combined my two reports for German public radio and added background information. If you are a German speaker or simply curious, you may want to listen to the original radio broadcasts here and here.