"Closed until victory"

The Second World War began 85 years ago. And the “sitting war" in French Alsace.

The war began on September 1, 1939 – in the East. The city of Strasbourg at the German-French border was evacuated on the same day. 400,000 people had to leave Alsace and Lorraine. Ghost towns, cats and dogs were left behind.

Mobilization

Friday, September 1, 1939: Paul Martin, Director of the History Museum in Strasbourg, writes in his war diary: “Mobilization. 4 p.m.: Evacuation of the population in the direction of the Dordogne.” Even before France declared war on the German Reich, a total of 400,000 people in Alsace and Lorraine had to leave their homes.

“We had to leave from one day to the next,” recalls Lina Grieswald, 81. She had only recently moved in with her parents with her nine-month-old son because her husband had been drafted into the army. Early in the morning, soldiers knocked on the door and told them they had to leave. “My brother and I were still young at the time and didn't worry too much,” says Lina, ”but it was really bad for our parents.” Her mother roasted a duck for the road. She cried as she did so. The baby carriage and a suitcase for the whole family were all they finally took with them. They drove as far as their petrol would take them in their own car, then continued like the other refugees by train, on wooden benches in the 4th class compartment. The last stretch in a cattle wagon.

Two days after the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 3, 1939, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. While the world watched the political developments with bated breath, all towns and villages in France within a three-mile-wide border strip along the Rhine and the Maginot Line were evacuated. This forced measure turned towns and villages into a ghost landscape. They remained deserted for nine months. A true exodus. Nevertheless, it happened almost unnoticed, as the eyes of the world turned to the east, where the Wehrmacht was raging a blitzkrieg.

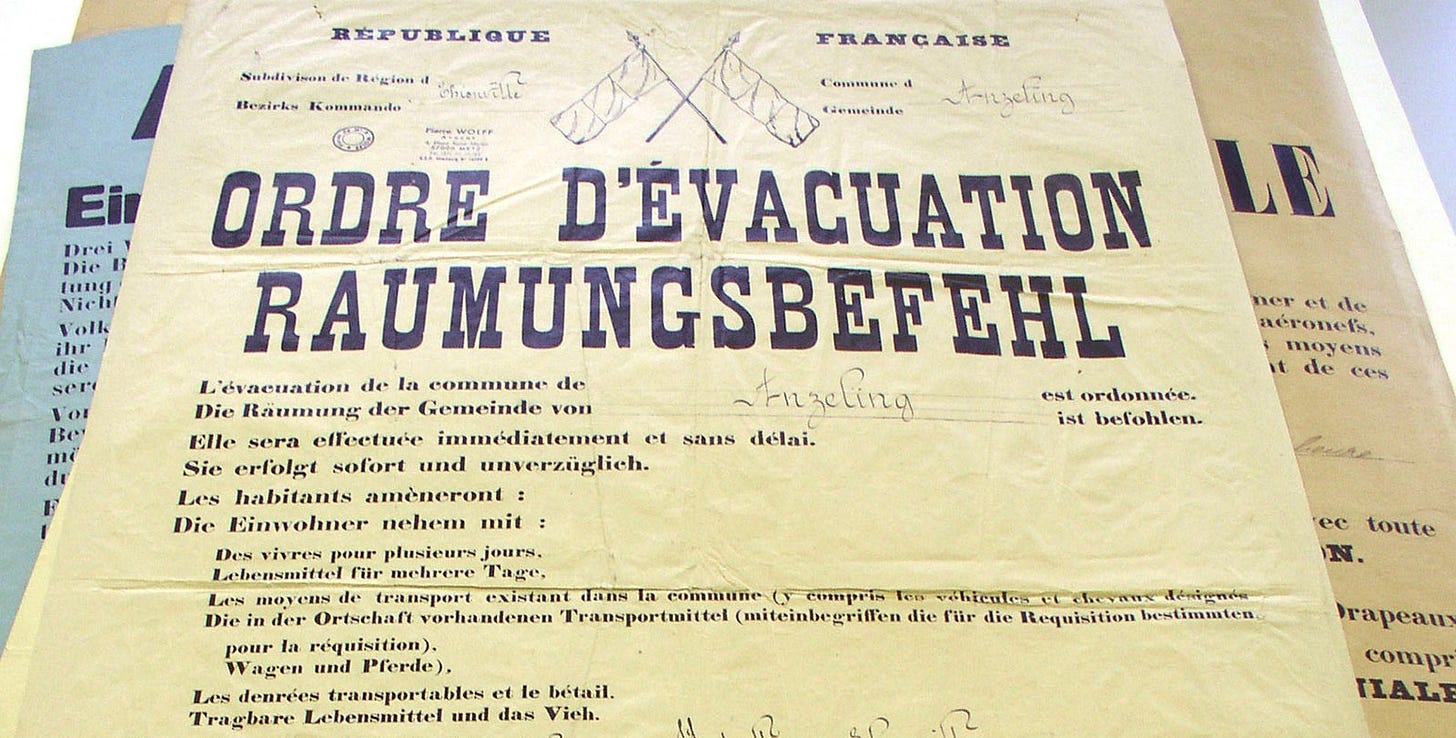

Residents in Alsace had 48 hours to leave their apartments, houses and yards. The authorities' decree was stuck to the walls of every house. “La drôle du guerre” began, the ‘strange war’, as the French called it. In German, a no less apt term was found: Sitzkrieg (sitting war). War was declared, but the weapons were at rest. In the 3rd French Republic, which was allied with Poland but shared a long border with the German Reich, the soldiers waited in the barracks for an enemy that never came.

Premonitions

According to a census, many of Strasbourg's 190,300 inhabitants had already left the city before the evacuation. The political developments spoke their own language. War was in the air. The year before, after the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland to the German Reich, 600,000 reservists had been called up in France. Although only for a week, since then the newspapers had been full of offers for houses in the Vosges and instructions on how to use gas masks. The economic situation in Alsace deteriorated noticeably as investment declined. The final impetus for many to move away was when the German army occupied the Czechoslovakian provinces of Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939.

Nevertheless, the evacuation came as a surprise to many people, as the authorities kept their plans secret. The plans had been in the works since 1936, when the German army marched into the demilitarized Rhineland. This act of violence brought back memories of 1870, when the German Empire had annexed Alsace. Something like that should not happen again. In 1939, both the civilian population and the art treasures were therefore brought to safety from an attack by the Wehrmacht.

The secrecy surrounding the evacuation fueled much speculation. Alsatian autonomists later suspected that it had even been the intention to relocate the entire population of Alsace - permanently. Was the evacuation perhaps also planned because the authorities feared that the Alsatians, who had belonged to Germany after the conquest from 1870 to 1918, would collaborate with the enemy? In the fall of 1939, the refugees were therefore initially met with suspicion by their “hosts”. Many locals, the French, considered the older Alsatians in particular, who did not speak a word of French, to be “boches” - a derogatory term for Germans.

On the road

Father Grieswald was attached to his farm and the animals. The family owned two horses, three cows, a dozen pigs and 500 chickens and ducks. He would never have left Strasbourg voluntarily. “We're staying here,” he said. But the eviction order was mandatory. Everyone had to submit to it. A notice stated: “From 6 p.m. on September 3, 1939, all persons found in the streets without a residence permit will be evacuated ex officio and immediately.” So the father said to himself: “I'll be right back”. He didn't even take a change of shirt with him. “That's why my mother had to wash his shirt every evening on the way so that he could put it on again the next morning,” says Lina. Her father was not allowed back.

The first trains with refugees headed for the Vosges left Strasbourg at 6 a.m. on September 2. As the men had received their call-up orders, there were almost only women, children and old people left in the city. They didn't know how long they would stay away. They had packed feverishly throughout the night. Each person was allowed 66 pounds of hand luggage. What to choose? The authorities' recommendations stated: food for four days, canned milk for the children, a pair of weatherproof shoes.

That same afternoon, the Grieswalds set off. The streets are teeming with people. Lina sees them hurrying past through the car window - on foot, with handcarts or, if they're lucky, on a horse-drawn cart. Fully loaded. Bundles of clothes and Singer sewing machines are piled up on bicycles. A priest carries a statue of the Virgin Mary in his arms. The refugees stream out onto the country roads like a train of ants. Pregnant women are among them, many of whom give birth in the ditch. The Grieswalds drive all day, always overtaking people, there were so many on the road. In the evening, the family reaches the first collection center, Bruyères, 75 miles away. There, the Red Cross distributes warm soup and milk for the children.

The “deserted” Strasbourg

Strasbourg is now ruled by the military. The mayor remains in the city for a while like the captain on a deserted ship. Finally, he shuttles between here and Périgueux, where Strasbourg's municipal administration has been evacuated. Other administrative units, the university, the two regional churches and the “Alsatian News” have also been relocated to other cities and are thus able to work. What remains in the “empty” city are the soldiers in the barracks, which are now full to bursting, as well as three hundred municipal employees and police officers who ensure the supply of electricity and gas and guard the buildings. Thanks to these precautionary measures, Strasbourg was spared from being plundered like the abandoned towns in the countryside.

“At the time, we all thought the war wouldn't last long,” says Francis Rohmer, smiling mildly in retrospect. At the time, the 92-year-old was an assistant doctor in the neurology department of Strasbourg's municipal hospital. The older doctors were already in the military and the patients, doctors and nurses had been transferred to the hotel in Hohwald, a small town in southern Alsace. “On September 1, the hospital was already empty”. It was very quiet in the large building when Francis Rohmer packed up his books and papers, as he had to join the army the next day. As a farewell, he “walked” through a city that was slowly barricading itself. The iron blinds were down in front of the stores. Sandbags were piled up in the window cavities of the cathedral and around the statues of Goethe and Kléber. A poster hung in a shop: “Closed until victory”.

Flocks of pigeons invaded the empty squares. “There were only cats and dogs in the streets,” says Charles Muller, who returned to the deserted town as a young lieutenant colonel. He had experienced September 1st as a summer visitor to the countryside. Now he wanted to see what had happened to his house. It was a gloomy day, sometime in the fall. Weeds were growing between the cobblestones and cracks in the wall. There was only one restaurant open, which served as the officers' canteen. In the city park where there was a small zoo, someone had unlocked the doors of the cages. The animals were running around freely. Charles Muller fetched a few bottles of wine from the cellar for his comrades. “The house was as I had left it. Then I left again.”

Far from home

The Grieswalds' odyssey lasted three weeks. From Bruyères to Périgueux. And on to the Vosges. The family finally arrived in the small village of Issac, which was to be their home for a year. While bathrooms were part of the standard of living in Alsace, there was no electric light or running water here. Not even an outhouse. “My father and brother then built us one”. Lina Grieswald laughs. “A zinc tub with a board with a hole in it. That was our toilet.” The only fireplace in the house was an open fire in the kitchen, through which it rained in. Her father covered it with a piece of sheet metal and also set traps for the rats. He won the trust of the villagers because he spoke French and - as a trained gardener - showed them how to prune trees.

More than eight months would pass before Paul Martin wrote in his war diary: “The Wehrmacht is attacking, devastating campaign in Belgium and Holland. This is the war!” On June 15, 1940, the first tanks of the expected army rolled across the Rhine at Colmar. Hitler's “Reich Governor” woke Strasbourg from its torpor.

A third of the inhabitants did not return to the occupied city. Instead of going “home to the Reich”, they preferred to go to more distant regions of France or, even further away, to Algeria, that time a French colony. Lina Grieswald's brother also went there. She herself returned to the farm with her parents. “Everything was ruined, the animals had been slaughtered and eaten.” Relatives bought her father a new cow. And he started all over again.

This text first appeared in German the Berlin newspaper “Tagesspiegel” in 1999 (read on my German website here). I am sure that this chapter of the Second World War is still as unknown to most people today as it was then. The idea for the story came to me by chance - in form of a subordinate clause in the novel “Les Nuits de Strasbourg” (Nights of Strasbourg) by Algerian writer, director and historian Assia Djebar. I read the novel because I was writing my book about Arab women filmmakers at the time. Unfortunately, I was not yet taking photos during my research and therefore don't have any photos of the protagonists.