50 years after Wounded Knee

In 1973, the American Indian Movement occupied the symbolic site. How do the Oglala Lakota live today?

Wounded Knee in South Dakota was the site of the last Indian massacre in 1890. The trauma continues to shape the descendants to this day. The Pine Ridge Reservation is still considered one of the poorest regions in the United States. What did the militant protest in 1973 accomplish?

Knocking at the parsonage of the "Church of God". Sylvia Hollow Horn opens the door - the wife of Pastor Stanley. The petite lady with the short hair tells what has been upsetting people here in Wounded Knee - on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota - lately: A snowstorm raged for eight days.

“Our water froze up. Luckily we had bottles of water. The snow was five feet high. So I slipped the door open, scooped and filled the bucket with snow, then I brought it in and melted it. I had to do that several times. Then we knew how much snow would flush a toilet.”

Others on the reservation had a similar experience. For some, the path to their dialysis treatment was blocked. Medications for Sylvia's husband could not be delivered. And what did the tribal chairmen do? Instead of helping in the chaos, they were 160 away at the annual tribal youth sports festival - in Rapid City, Sylvia Hollow Horn laments.

“People said: The whole council was up there. They scheduled a meeting and they were all there in hotel rooms. They knew this storm was coming just as we knew it was coming. I feel and many people feel somebody should have stayed home.”

Instead, South Dakota's Republican, non-Indigenous governor, Kristi Noem, sent the National Guard to help, clearing snow and transporting firewood onto the reservation.

The Pine Ridge Reservation of the Oglala Lakota is slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Maryland and sparsely populated. Between 20,000 and 30,000 residents. The landscape is gently rolling with the picturesque rock formations of the "badlands" in the northeast. Fifty years ago, reporters from all over the world flocked “to the rez”.

News of the occupation of Wounded Knee made headlines around the world: On Feb. 27, 1973, some 200 young Oglala Lakota and members of the American Indian Movement set out. Men and women were among them. They set up roadblocks with their pickup trucks, ransacked the local museum and the only trading post in town run by a white family, then barricaded themselves in the church for weeks. Kathy Eagle Hawk was 21 years old at the time.

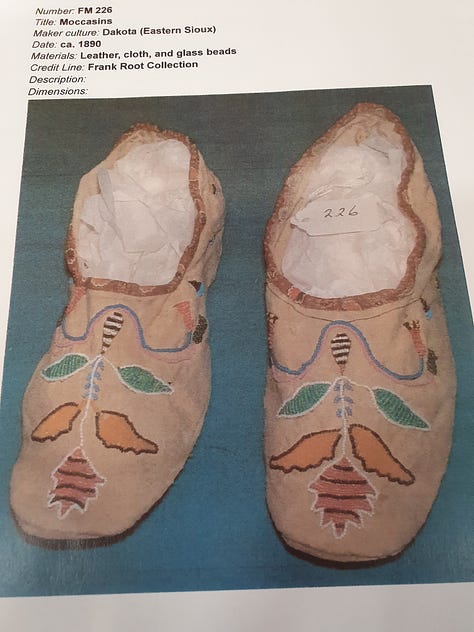

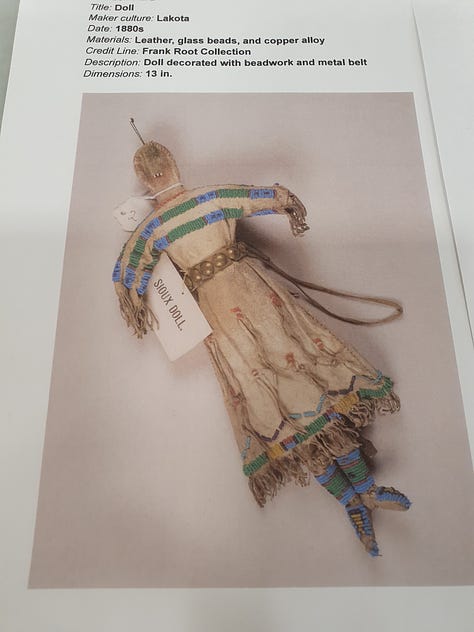

“My grandmother actually did business with the Guildersleeves there. She made belts, hair ties, earrings, beaded mokassins. And she took them over to the trading post, and they would give her food and kerosene for our lamps. She would feel bad when we watched how everybody looted the place.”

Nevertheless, this was not an occupation, as it is officially called, says Kathy Eagle Hawk. Rather, it was a desperate protest against the tribal president, Robert "Dick" Wilson, who was considered corrupt.

The tribe's official representative, though elected by residents, reports to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington - and that to the U.S. Department of the Interior. Many Lakota see this as an extension of the U.S. government. The true "tribal chiefs" are considered to be the traditional leaders, who are not elected according to Western rites, but who are distinguished by their character, wisdom and spirituality.

At that time, in 1973, it would also have played a role in the conflict that tribal president Robert Wilson was a "half-blood Lokata," Kathy Eagle Hawk says.

“He was against full blood Lakota people. He put a stop to the Sun Dances and powwows and other ceremonies. He had his own people who threatened families. So the elders called AIM. They had meetings with them, and decided to go and take over Wounded Knee.”

The event contributed to the visibility of the new native identity. Five years before the protest or occupation, the American Indian Movement emerged - in the city of Minneapolis in the state of Minnesota. The activists wanted to draw attention to the high unemployment rate among the indigenous population, the housing shortage, the discrimination. This also attracted Regina Brave:

“They had this really nice mission statement: no alcohol, no drugs, no womanizing. Help the people and stand up for the people and so forth. But it really wasn't that way at all. I know this because I followed them, that's why I ended up in Wounded Knee.”

Regina Brave grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation. At the time, life expectancy for men was 47 years. 80 percent of the residents were unemployed, many alcoholics. Domestic violence is an everyday occurrence. The year before the occupation of Wounded Knee, two Indians had been murdered by whites, and the prison sentences were moderate. After the second verdict, AIM supporters burned down the chamber of commerce in the small town of Custer in protest. Anger at the "white man," as Russell Means, the most prominent spokesman for the American Indian Movement, puts it, is high:

“Hey listen, white men: I have had all the bullshit from your race as I can take.”

The U.S. authorities quickly respond to the occupation, during which the activists also take white people hostage. At least according to the official version, though activists at the time deny it to this day. U.S. marshals, the FBI, the National Guard with snipers, tanks and helicopters arrived the next morning, explains Regina Brave who remembers many an anecdote:

“Most of these young people who came in from Minnesota with AIM came from urban areas and did not even know how to use a gun. One of them shot a hole through his foot because he was bouncing that gun on his foot, and the safety was probably off. Another one was doing it with his hand over the barrel. That was how dumb they were. We rounded them all up and taught them how to take a gun apart and keep it clean.”

The site at Wounded Knee was already a symbolic one. Here, on December 29, 1890, one of the last massacres of American Indians in the United States had taken place. The great chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were already dead. Chief Big Foot and his trek were stopped in a blizzard by U.S. cavalry. As they were disarmed, a shot rang out from the rifle of a deaf and dumb Lakota who would not surrender his weapon. From a hill, soldiers of the 7th U.S. Cavalry opened fire. They shot between 200 and 300 Lakota and buried them in a mass grave. Most of them were women and children.

In 1973, the U.S. government of the time under Richard Nixon wants to avoid a second massacre. Instead of storming, they negotiate. During the day. At night, U.S. forces and occupiers engage in fierce gun battles. The activists are demanding better living conditions, a renegotiation of broken treaties, an investigation into the murders on the reservation - and the removal of tribal president Wilson. Through surreptitious channels, more and more Indians are arriving from other states in support. For many of them it is the first time to come into contact with traditional native culture and language.

In Hollywood, actor Marlon Brando refuses to accept the "Oscar" he is to receive for his role in the film "The Godfather" - out of solidarity. A poll shows that most Americans are on the side of the occupiers. AIM spokesman Russel Means eventually proclaims an independent Oglala Lakota Nation on the territory of Wounded Knee. A delegation even travels to New York City but the United Nations refuse to recognize their sovereignty.

The tide turns. A young Lakota is shot and killed, and a U.S. marshal remains paralyzed. The U.S. government turns off the occupants' electricity and water. When a second young Lakota is shot, the tribal elders give up. After 71 days, on May 8, 1973, the occupiers leave - without their demands being met.

Tribal President Wilson remains. Both sides take bloody revenge over the next few years. At least 60 supporters of the American Indian Movement are murdered. So are two FBI officials. And an alleged FBI accomplice from the Indians' ranks. Local resident Martha American Horse, then 14 years old, recalls:

“Before AIM left they burnt the store and the museum down. The white people who owned the store had houses where they lived in, they burnt them all down.”

As a result, Martha's uncle loses his job in one fell swoop. Residents have to travel to the town of Pine Ridge, a half-hour drive away, to do their shopping. Many do not have their own car. And so resentment quickly arises over the destruction. To this day, the Oglala Lakota are divided over the militant actions of the time. the followers of AIM have been celebrating February 27 as "Liberation Day" ever since.

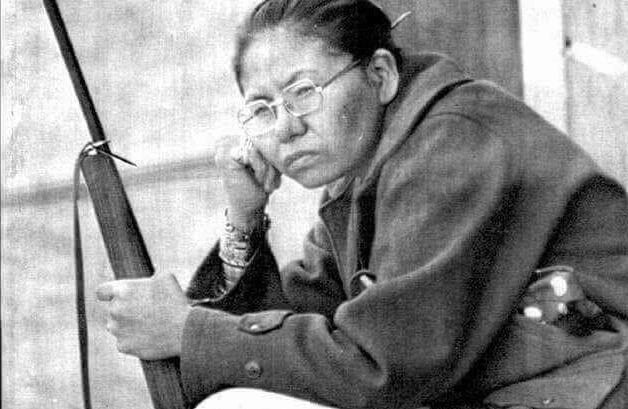

Regina Brave, whose photo with a rifle over her shoulder was on almost every front page in the USA in 1973, is disillusioned:

“Over time AIM started romanticizing the occupation of Wounded Knee. It was nothing romatic about the occupation. We were shot at. The weather was cold. We had 206 people who were charged out of Wounded Knee, the non-leadership, the real warriors, who were standing bunker duty. These guys, the so-called leaders, occupied a trailer home down below and were just eating real good while the rest of us was practically starving.”

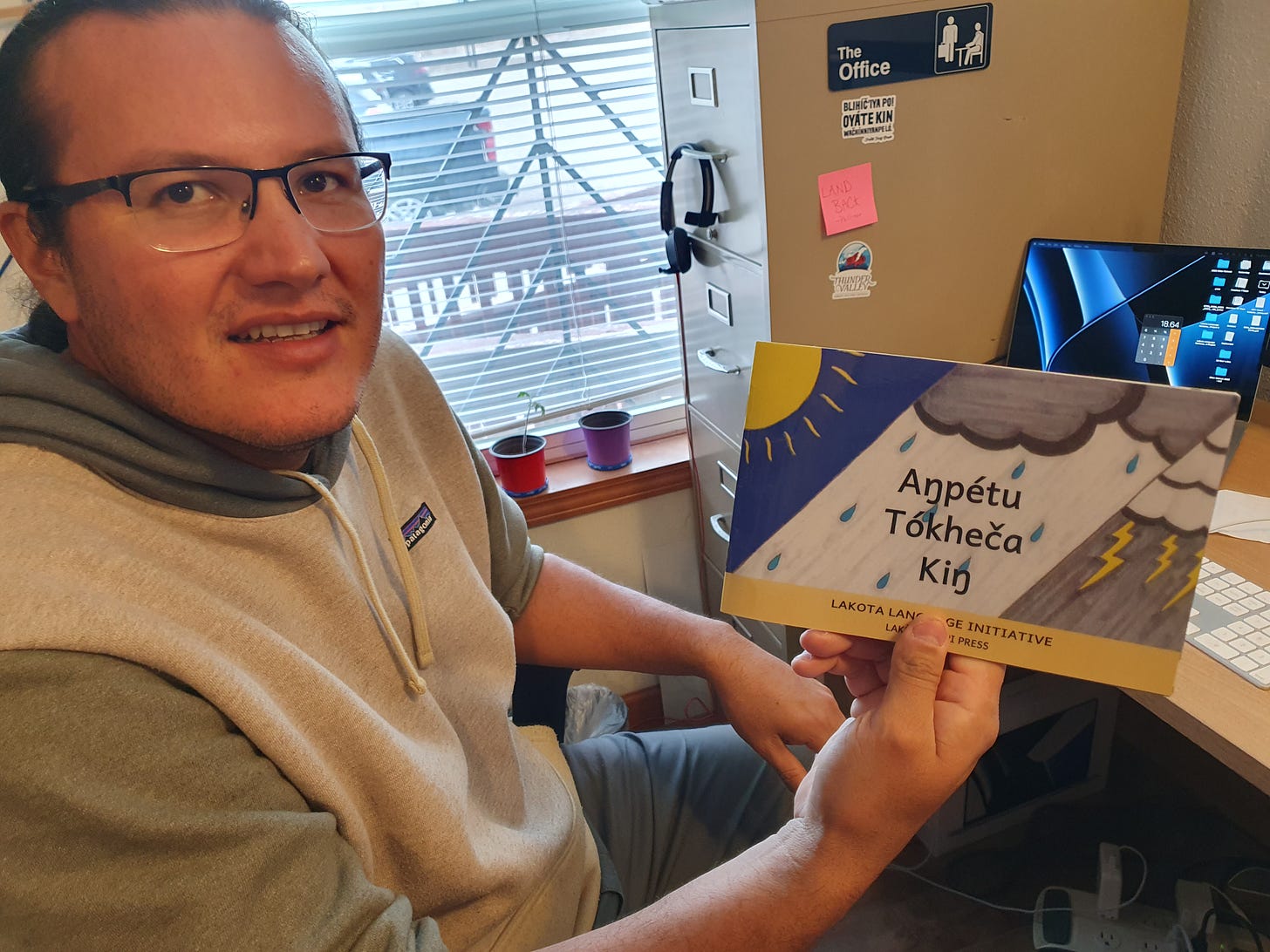

And nowadays? Not far from Wounded Knee, there is now a pioneering project of the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation. A model village where the Lakota are once again allowed to speak their language, explains Dallas Nelson. He heads the language project, proudly wears the typical long braid of Lakota men and is grateful for the activists of the 1970s.

“American Indian Movement made it cool to be Lakota during the time when it was frowned upon, and you were put in jail. They put it front and center to have long hair, speak your language, to practice your ceremonies. I am 35 years old and my wife is 33. Our parents where at the protests. Now we are given the opportunity because of their effort to have places like our Montessori nursery, a place where we can relearn our Lakota language.”

His parents, Dallas Nelson explains, both attended so-called boarding schools where only English was allowed to be spoken for the purpose of assimilation. He himself therefore learned Lakota only as an adult.

Nelson points out the window to a row of colorful square houses reminiscent of Norway. With the Thunder Valley project, the young Lakota says, he and his fellow volunteers wanted to build a community that lives in a socially and environmentally sustainable way. Just like their ancestors once did, who migrated with the buffalo herds and had to settle down on the reservation.

In one of the colorful houses lives Darwin Begay, a Navajo from Arizona. His wife is an Oglala Lakota from the reservation. She is not at home at the moment, and the young father is in the process of diapering one of his small twin sons. “During winter time I am the house man. My wife is a photographer and works from home sometimes. I am a fire fighter. I fight fires across the United States and I travel a lot.”

Darwin Begay and Dallas Nelson are a new generation. Which definitely causes skepticism among the tradition-conscious elders. Traditionalists and modernizers are united in recalling their common historical heritage: the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. On each anniversary, a ceremony is held at the burial site.

On this 29th of December, more than a hundred people are gathered next to the graves. Young and old. A tribal elder burns incense in a clay pot and says a prayer.

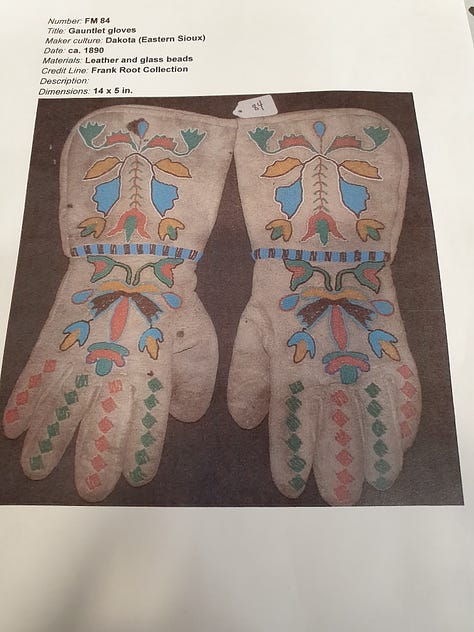

This time he also blesses some original relics of the 1890 massacre. The items had been repatriated from a museum in Boston shortly before. Articles of clothing, embroidered moccasins, pendants. Soon the relics will be on display at the reservation's community college museum.

The reservation has a local radio station that also broadcasts in the Lakota language and celebrated its 40th anniversary in February. A Pizza Hut has opened in Pine Ridge, the administrative center, and a Taco Drive-In. On the rest of the reservation, many homes are still without running water or sewage disposal. Sylvia and Pastor Hollow Horn have allowed affected neighbors to tap spring water from a faucet on their property.

“The people who owned that land were roughed up by the American Indian Movement during the occupation. They kind of terrorized them because they were non-natives. I think there son in law ended up being the only heir alive. He didn't have very good feelings for the tribe naturally. So he wouldn't sign that easement.”

Unemployment, alcoholism, drugs, domestic violence and broken families are still part of everyday life “on the rez”. The South Dakota county is considered the poorest in the United States. In front of many houses, residents have piled up belongings - fearing that their money might not be enough to buy something new. Inside many houses, too, it looks like a junk room.

The poverty is partly connected to an anti-attitude toward the U.S. government. Because, according to the treaties of 1868, Washington distributes the money to the tribal administration according to the number of registered inhabitants. Many Lakota do not want to register because they reject the control of the government. Accordingly, the hospital on the reservation, for example, receives less money. And like tribal President Wilson in 1973, his successors have a reputation for being corrupt and operators of nepotism.

On the streets of Pine Ridge - the administrative center with about 3000 inhabitants - youth gangs are now also roaming the streets and regularly engage in gunfights.

In the center of the city, next to the post office and gas station, two aid projects take care of the many homeless people. One project has a 24-hour suicide hotline. It all looks like little hope for the young Oglala Lakota. Dallas Nelson of the Thunder Valley Project therefore looks far into the future:

“I whole heartedly recognize that a lot of things I'm dreaming of I probably won't see in my lifetime. And I do hope that when ever I leave this place I sat it up for the next generation that continues to push it forward in ways that I couldn't even dream of. We call this the 7-generation philosophy: we have to continue our plan looking three generations back and three generations forward. That to me is sustainability.”

The story originally was published in German as radio features on Austrian Radio and German national public radio and can be listened to on my website.